Die 6 ianuarii Anno Domini 2026

In Epiphania Domini

In early November of last year, Italian government institutions, as well as numerous press and television agencies, including the official channels of the Holy See, reported the recovery of a stolen (or lost?) papal manuscript from the first half of the 19th century by state authorities. The announcement generated considerable publicity and was picked up by professional portals and Catholic media from around the world, including Poland. Since the recovery of this manuscript was made possible indirectly thanks to us, we will attempt to take a closer look at this matter and describe it in a broader — though still not entirely clear or satisfactory — context.

I. What manuscript are we actually talking about?

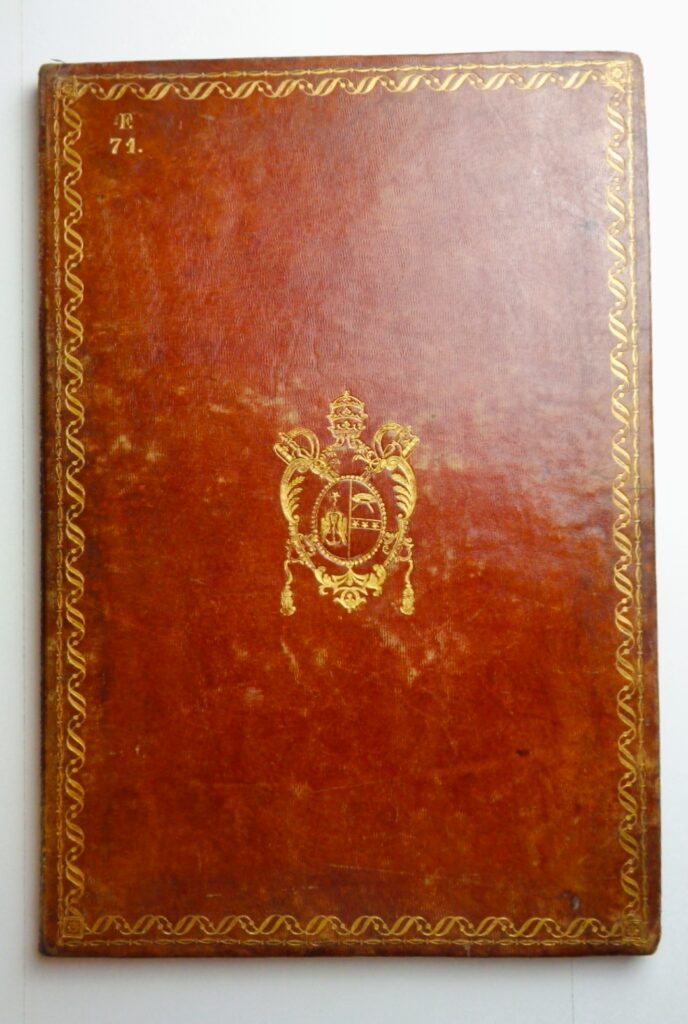

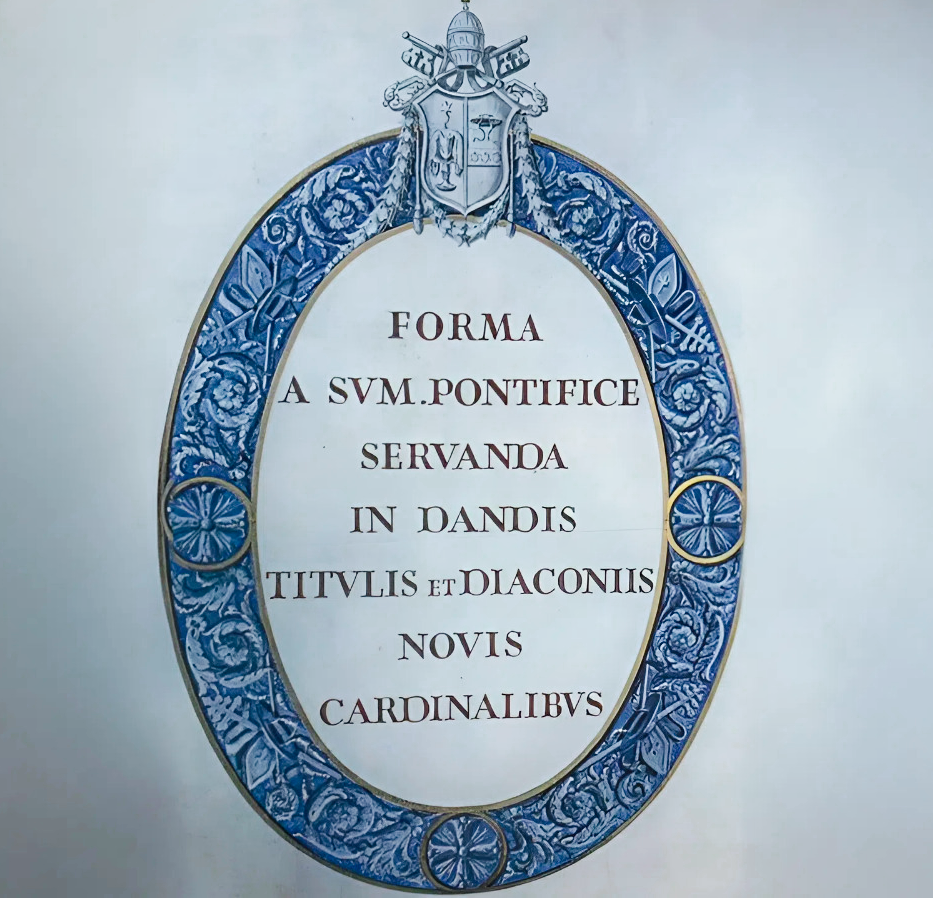

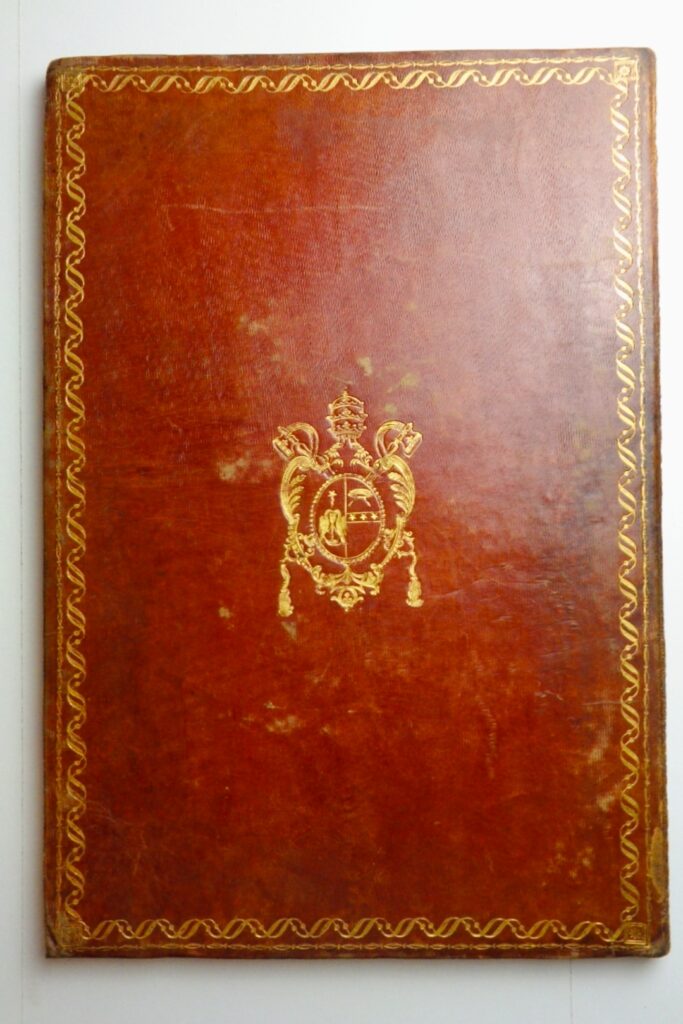

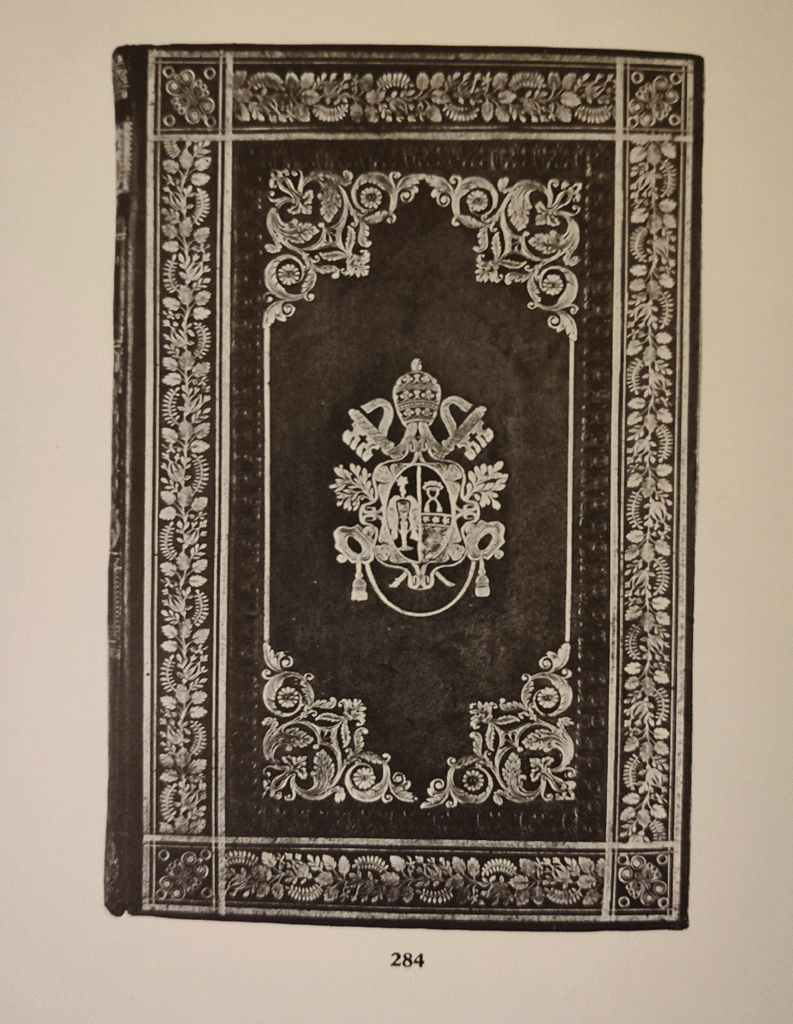

The subject of all this commotion is an extremely valuable manuscript — especially from the perspective of papal ceremonies and their history in the 19th century — entitled Forma a Sum.[mo] Pontifice servanda in dandis Titulis et Diaconiis novis Cardinalibus, written in the first half of the 19th century. The exact date of its creation cannot be determined, but considering that the coat of arms of Pope Gregory XVI appears on both sides of the decorative binding, and that the manuscript was included in the 1864 catalog of the Archive of the College of Papal Masters of Ceremonies (Archivio de’ Maestri delle Cerimonie Pontificie), it can certainly be assumed that it was used during the creation of cardinals by Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari. It is possible that it was also used by later popes, until the end of the first half of the 20th century. Its later fate is shrouded in some ambiguity, which we will discuss below.

Source: press materials and antique bookshop archives.

The manuscript is substantial, measuring approximately 30 cm wide and 46 cm high, which clearly indicates its ceremonial use. Inside, there are 48 unnumbered folio pages, on which are written, above all, the activities and prayers recited by the pope during the conferral of cardinal titles and diaconates (i.e., Roman titular churches) on newly appointed cardinals. The solemn conferral of titular churches, combined with the presentation of cardinal rings, was the final element of a rich ceremony, divided into several stages, in which the Pope created the highest Roman ecclesiastical dignitaries.

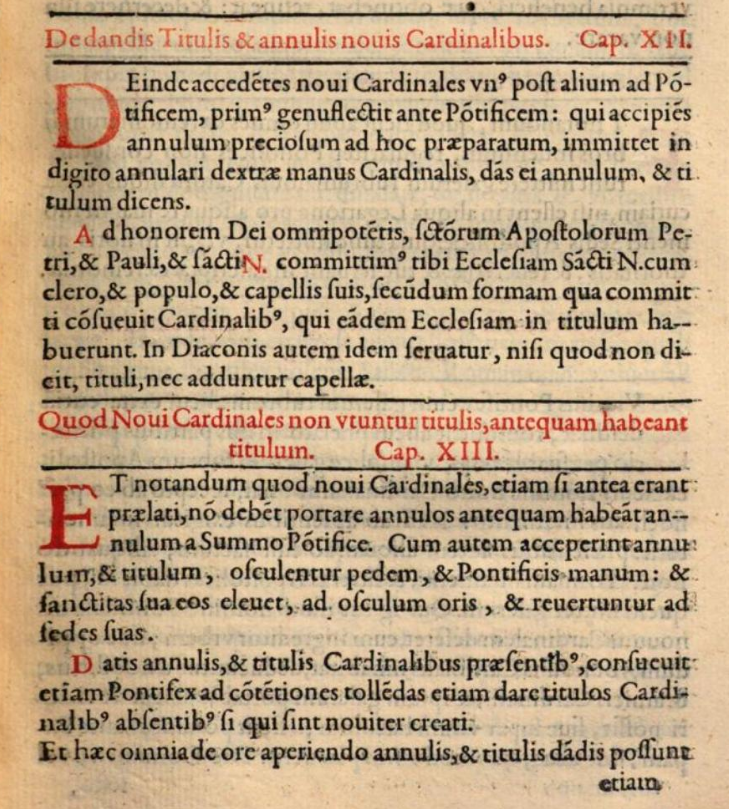

When handing the cardinals a handwritten scroll enshrined in a special tube, the Pope pronounced the words: Ad honorem Dei Omnipotentis, Sanctorum Apostolorum Petri et Pauli et Sancti N. commitimus tibi Ecclesiam Sancti N. cum clero et populo et capellis suis, secundum forman qua committi consuevit Cardinalibus, qui eandem Ecclesiam in titulum habuerunt (in the case of cardinal deacons, he omitted the words „capellis” and „titulum”). This formula was established in Piccolomini’s famous papal ceremonial (15th-16th century) and survived into the second half of the 20th century. A similar, but much shorter formula is currently in use.

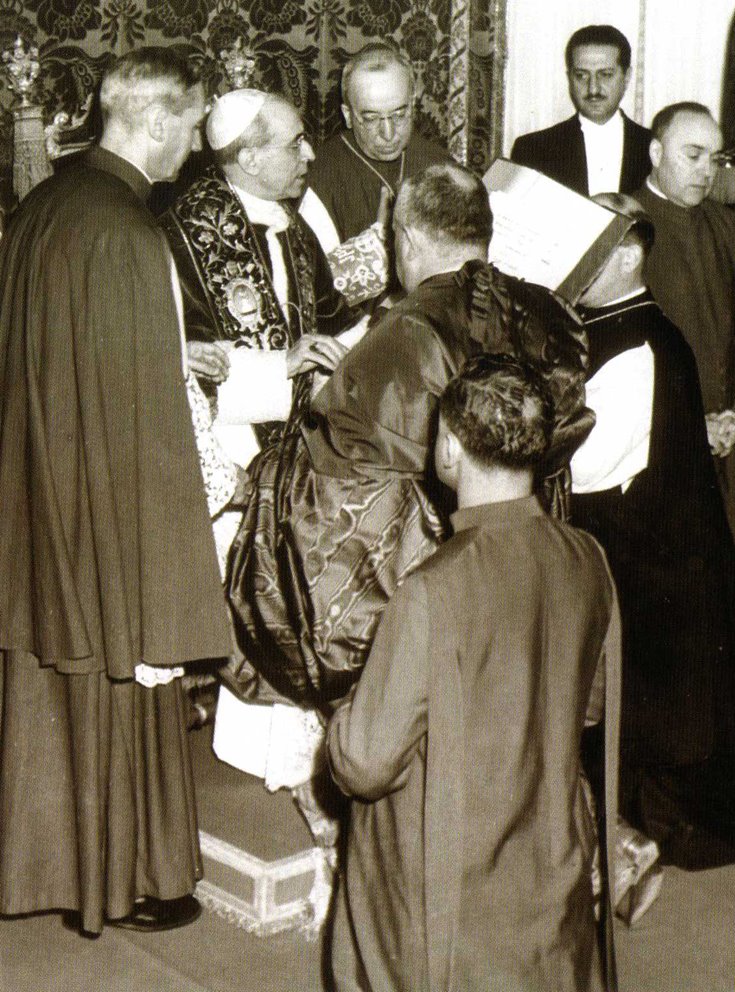

In the photo on the left, we see Pope Pius XII presenting the cardinal’s ring and the document granting a titular church (in this case, St. Augustine’s: Basilica di Sant’Agostino, granted to cardinal priests) to Cardinal Francisco Quiroga y Palacios. Kneeling before the Pope on the left is the papal sacristan, Archbishop Petrus Canisius Jean van Lierde, the last papal sacristan in history (Sacrista del Palazzo Apostolico). In his hands, he may be holding the recently discovered manuscript F.71. A clue supporting this thesis is the fact that in the manuscript, in place of some of the names of titular churches, there are long, blank pieces of paper, indicating the book’s repeated use during papal ceremonies.

II. What actually happened?

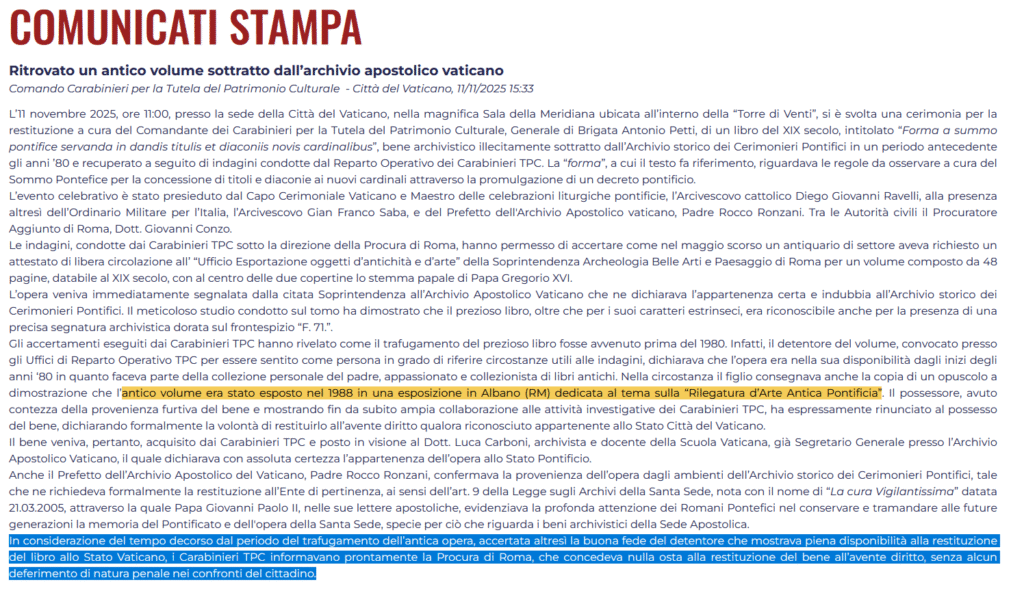

The book had been on offer at a Roman antiquarian bookstore since at least the first half of 2024. That’s when we first contacted the seller to gather information about several items, including the manuscript en question. The actual request for quotation for this book was submitted on March 30, 2025, and a deposit of one-quarter of the agreed price was paid the following day. The following day, the antiquarian submitted an export request to the relevant Italian government office (Ministero della Cultura). Local regulations generally prohibit the free export of works that may be considered cultural property; in the case of books, the caesura is considered to be 1900. This is standard procedure, and generally, if no problems are detected (e.g., an item appearing on a list of stolen and wanted works), an export permit is issued. This was the case here for a while. On May 13th, we received a message from the seller informing us that the day before, a designated commission had inspected the transaction and that no complications were expected, so he would be preparing the book for shipment. On May 22nd, we received another message in which the seller noted that the commission had not yet issued permission and expressed concern that it was taking so long (usually a formality). In a subsequent message, received on June 6th, we were informed that the seller had received information the day before that the book had been held by the office for further verification. Just over a month later, on July 15th, we received an email from an antiquarian book dealer informing us that the export, and therefore the entire transaction, had been blocked by the Office of Papal Liturgical Celebrations, which requested the return of the manuscript. Importantly, the antiquarian book dealer stated in this message that he was confident that he had legally acquired the book, as evidenced by the fact that the sale had been reported to the Ministry of Culture and his subsequent cooperation with Italian and Vatican authorities. Less than four months later, news of the recovery of the precious manuscript by the Carabinieri from the Cultural Heritage Protection Unit was published. As announced at the time, its ceremonial handover to the Vatican Apostolic Archives was set for November 11th. Since the order had been paid in full in the meantime, all funds were kindly refunded by the seller in July. The seller has declined to comment further on this matter at this time because, according to his information, the official administrative procedure had not been completed as of December 31, 2025.

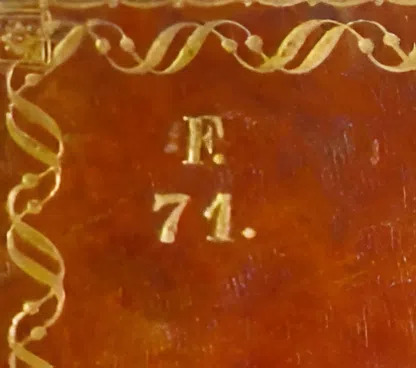

As stated in official announcements, Professor Luca Carboni, a long-time employee, lecturer, and current Secretary General of the Vatican Apostolic Archives, stated with absolute certainty that the manuscript in question belonged to and was stolen (lost?) from the Holy See, as evidenced by the gold-embossed designation F.71. The manuscript’s authenticity was also confirmed by the Prefect of the Vatican Apostolic Archives, Father Rocco Ronzani, OSA, a religious brother of Pope Leo XIV.

On November 11, the ceremonial handover of the manuscript took place, attended by numerous prominent figures and officials (including the Master of Papal Ceremonies, Archbishop Diego Ravelli). It featured addresses and speeches from, among others, Archbishop Giovanni Cesare Pagazzi, Archivist and Librarian of the Holy Roman Church, and Archbishop Gian Franco Saba, Military Ordinary of Italy. The meeting took place in the Meridian Hall (Salla della Meridiana) in the Archives. The manuscript was personally handed over by Brigadier General Antonio Petti, Commander of the Carabinieri for the Protection of Cultural Heritage.

III. Stolen or lost?

Press releases and journalistic reports state that manuscript F.71. was stolen (lost?) in the late 1980s. It is repeated like a mantra that it was presented during an exhibition entitled La rilegatura d’arte antica pontificia, which took place in 1988 in Albano (in the province of Rome, just “under the nose” of the Vatican). However, it is futile to look for any information about this exhibition, apart from other books that were exhibited at the time and are now available for purchase (their descriptions include information about the exhibition; importantly, they are all offered by the same antique bookshop).

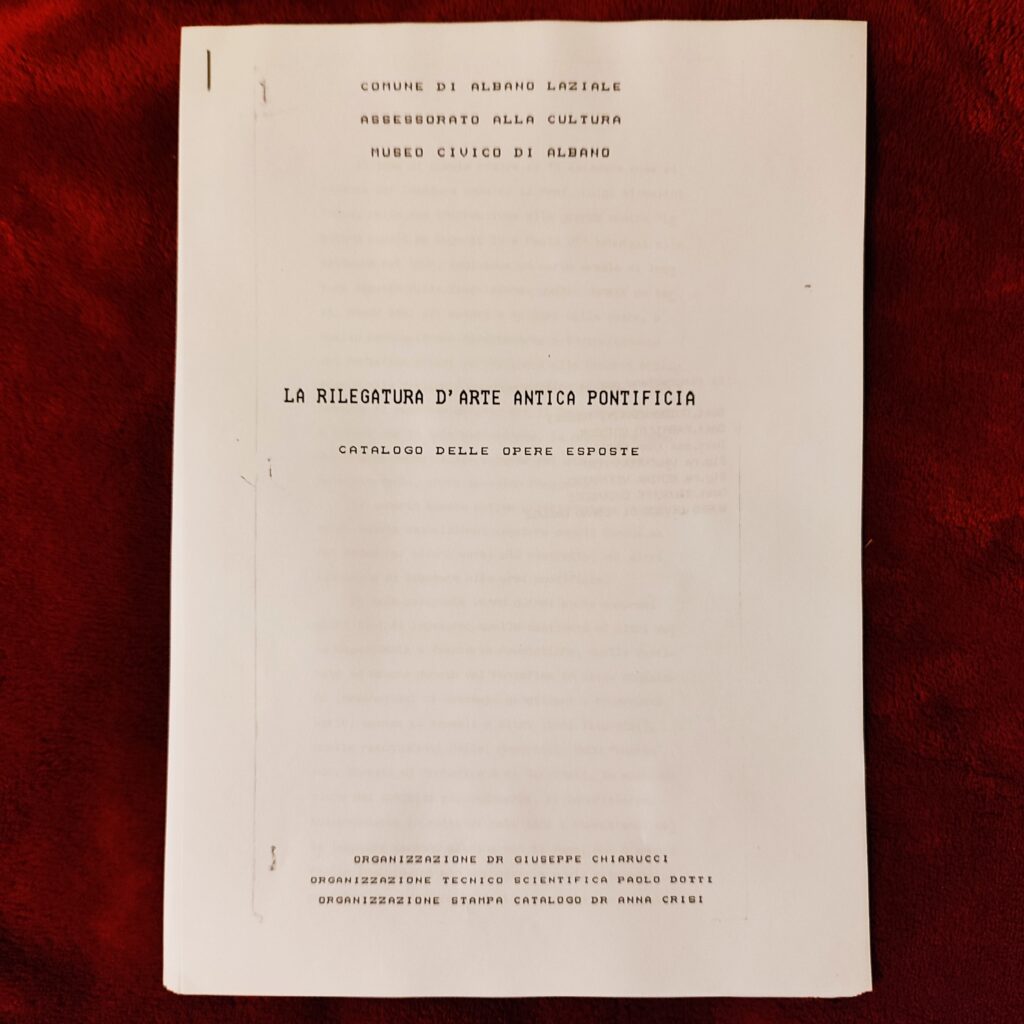

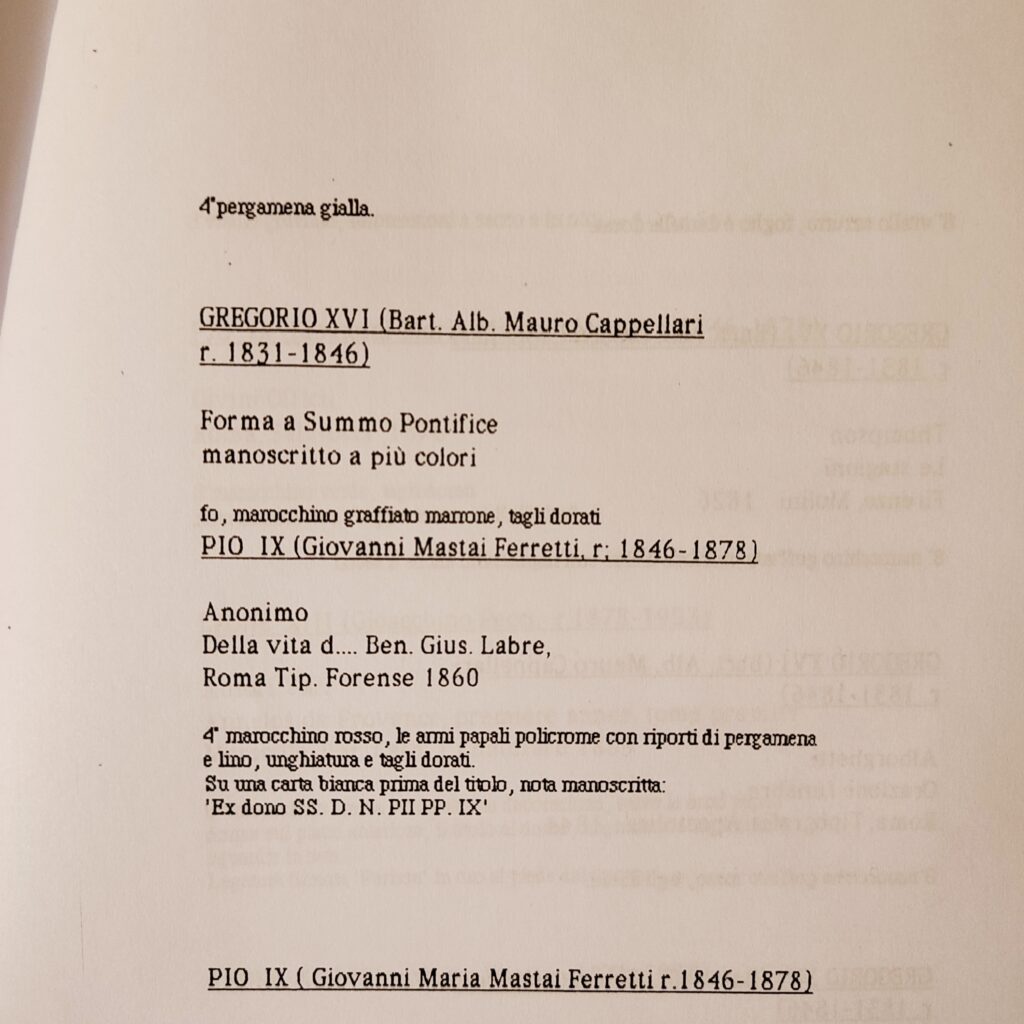

However, we have a copy of the exhibition catalog, which lists nine books in decorative bindings bearing the coat of arms of Pope Gregory XVI, including manuscript F.71. described as Forma a Summo Pontifice, manoscritto a più colori, fo[lio], marocchino graffiato marrone, tagli dorati (no page numbering or exhibit numbering). The institutional organizers of the exhibition were the Department of Culture of Albano (Assessorato alla Cultura, Comune di Albano Laziale) and the local museum (Museo civico di Albano). Those responsible for the actual organization were: Dr. Giuseppe Chiarucci (main organizer), Paolo Dotti (technical and scientific organizer), and Dr. Anna Crisi (responsible for the catalog). The author of the introduction to the catalog was Guido Vianini Tolomei. The catalog includes 79 items. Several of these can still be found in the antiquarian bookstore. It was after the exhibition that the manuscript was allegedly stolen – this was the story officially announced and then taken further, with simultaneous journalistic deprecation of the “private collectors” who had deliberately hidden the manuscript for decades.

However, should we unequivocally refer to this as theft? Press reports and journalistic communications indicate that the antique dealer cooperated fully, openly, and voluntarily with the authorities in order to resolve the matter (which turned out to be negative for him, as he suffered financial losses, but fortunately avoided legal consequences). Moreover, as mentioned, he was convinced that he had acquired the book completely legally (along with some other items from the exhibition, he inherited it from his father, who was a collector of old books). What is more, he himself reported its sale to the competent authority and was initially confident that there would be no problem with shipping it abroad. When the problem arose, he refunded the entire amount for the book without hesitation. The antique dealer’s attitude should therefore be considered honest and transparent. All the exhibits he offered from the exhibition, including manuscript F.71., were or are properly described and presented (e.g., characteristic marks are not covered). What is more, this manuscript, like other items from the exhibition offered by the antiquarian bookshop, was made available with a full description and photographs not only on the bookshop’s website, but also on well-known book sales portals. Until the intention to export was reported, none of the officials or researchers had taken an interest in the manuscript.

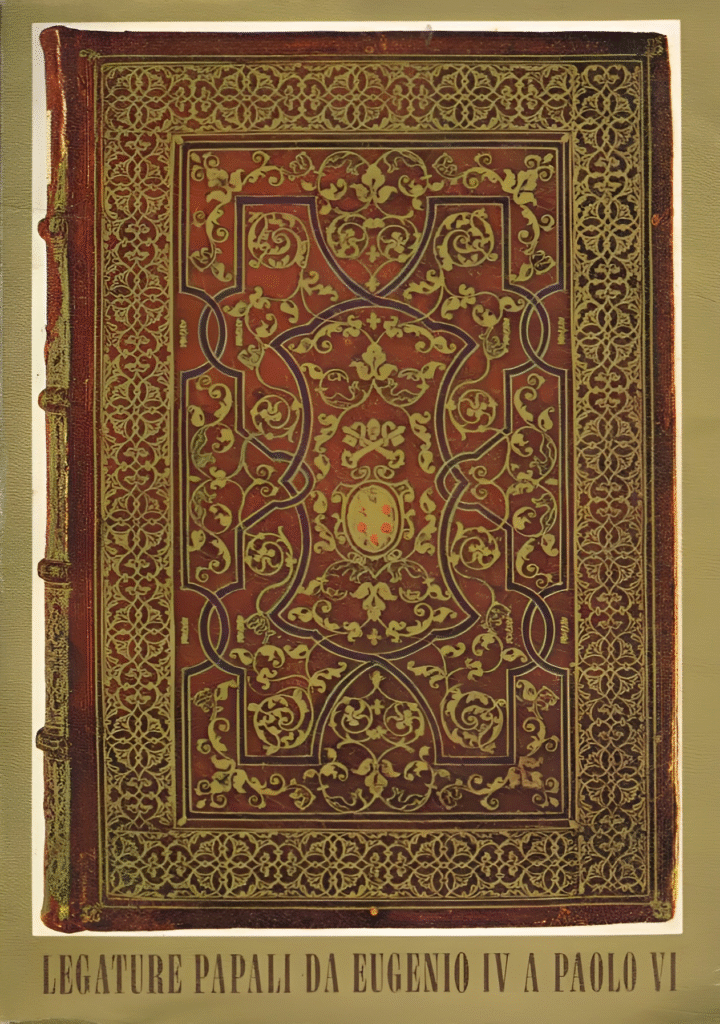

It is interesting to note that manuscript F.71. was not included in the famous and, to date, probably the largest exhibition devoted to artistic papal bindings: Legature papali da Eugenio IV a Paolo VI (Vatican 1977). The exhibition catalog includes 302 items, including six with the papal coat of arms of Gregory XVI. The exhibition and the publication of the catalog were prepared thanks to the efforts of, among others, Cardinal Alfonso M. Stickler SDB, then Prefect of the Apostolic Library and papal pro-archivist.

IV. Questions (still) without answers

Several questions arise that need to be answered in order to understand the proper context of the whole matter. First of all: was the disappearance of manuscript F.71. from the Vatican collections noted before or after the 1988 exhibition in Albano? If before, why did no one react when it appeared in Albano? If after the exhibition, when exactly? Have all the items borrowed from the Apostolic Archives been returned to their place, and if not, how many specifically have not been returned and why? If so, who controlled the loan? Why did the sale of the manuscript go unnoticed for many months by officials (both state and church) and those involved in the recovery of lost or stolen cultural artifacts, especially those of such (in)valuable importance, especially since the book was located in Rome the entire time? How is it possible that the book, while remaining in Rome and being offered for sale to the public, did not attract anyone’s attention? Why did anyone react only when the book was “served on a plate,” given that in such cases officials have the tools to recover cultural property without the need for its current owner to officially report it? Would anyone have taken any steps to recover the book if someone from outside Italy had not wanted to buy it? The list of questions could be much longer.

It should be added that similar books, often in priceless artistic papal bindings, are offered by many different sellers and antique dealers on sales and auction websites, as well as at prestigious auctions (example: here). How is it that so many (priceless) cultural treasures directly related to or even once belonging to the Holy See leave its collections and archives and do not return to them? Is it really all the fault of collectors, antique dealers and auction houses?

A somewhat bitter reflection arises: it seems that if it weren’t for the honesty of the antique dealer, none of the representatives of the state apparatus and the Church would have been able to trumpet their spectacular success, high-ranking officials and dignitaries would not have been able to exchange smiles and handshakes, and no one would have stood in the spotlight to talk about the effectiveness of procedures and actions taken. Might there be justifiable concerns that the entire situation is the result of avoidable negligence, rather than a deliberate and premeditated theft?

V. Instead of a conclusion

We hope that in the future, manuscript F.71. will be carefully digitized and made available to researchers and enthusiasts of papal ceremonies from around the world, for the glory and benefit of the Holy Church. Ut in omnibus Deus glorificetur.

RECOMMENDED VIDEOS

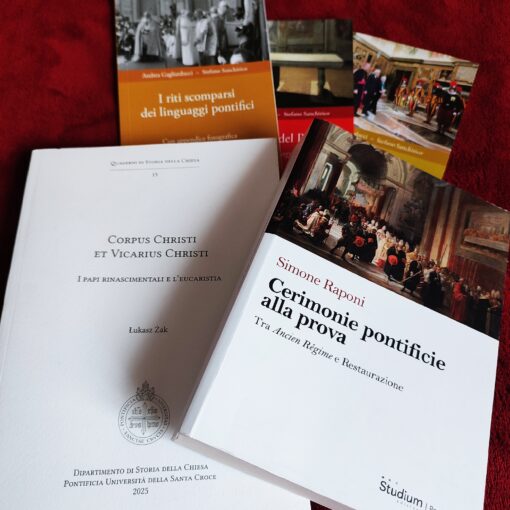

RECOMMENDED READINGS

- Pope John Paul II, Apostolic Letter in the form of a motu proprio La cura vigilantissima of 21 March 2005.

- Legal Decree of 22 January 2004, n. 42, known as Codice Urbani or Codice dei beni culturali e del paesaggio.

- Legature Papali da Eugenio IV a Paolo VI, presentation: Cardinal Alfonso M. Stickler SDB, „Cataloghi di Mostre” 21, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano 1977.